“The idea came from a general meeting about our safety efforts,” said Brian Gigoux, vice president of equipment and maintenance at Enid, Okla.-based Groendyke Transport. “We had made an investment to acquire all of our new tractors with collision mitigation systems and forward-facing radars. We were very impressed with the results and decided to tackle the next problem: people running into the back of us.”

The company started testing strobe lights on a limited basis, going out after dark to its terminal yard and retrofitting some trailers with lights from different manufacturers and intensities, and choosing the ones they thought would be satisfactory.

“We were very cautious that the light could be so overwhelming, that it could actually cause a problem, especially in inclement weather like snow. We tested in three locations—Kansas City, Denver and Fort Worth—and got some driver feedback. It evolved from there,” explained Gigoux.

Drivers said they could tell when their trailer was equipped with a strobe. They saw a difference in watching the traffic behind them start to make lane changes sooner and that other drivers seemed more attentive. Once the company started tracking data, it agreed with what the drivers were noticing.

“The strobes were unique enough that they got people’s attention, [alerting them] that something ahead is getting ready to change,” Gigoux noted.

He added that drivers didn’t want a continuous light like those found on vocational trucks or blinking white strobes found on school buses because people see them all the time and become complacent. Although the company didn’t use the services of an industrial psychologist to suggest the optimum blinking rate, color or position, trial and error, driver feedback and data indicated what worked best.

“We played around with the placement of it and the intensity of the lighting. Then we tried some different programmable strobes that have a real fast intensity, but the one we’re using now blinks about 73 times per minute,” Gigoux said. “It’s a little bit more than once a per second. We feel like it’s just very effective.”

The choice of amber also seems to work well because of how drivers have been trained to determine a situation based on colors they see on the road.

“We associate amber or yellow with hazard or warning,” said Ryan Pietzsch, driver safety education expert for the National Safety Council. He has not reviewed the Groendyke study. “Flashing lights and specifically certain colors, red lights (fire vehicles), blue lights (law enforcement), and white lights (strobes on school buses) are associated with certain vehicles (depending upon the state), and we need to keep that uniqueness for them for emergency purposes,” Pietzsch emphasized. “As far as the amber goes, you’ve seen construction vehicles with amber flashing lights and vehicles that operate around a roadway will have them. Most state laws allow for the use of hazard lights below the posted minimum speed limit, for example. If you’re operating and you’re truly a hazard, like an oversized load, they use flashing amber lights, and, oftentimes, they have escort vehicles with flashing amber lights. The intent is to get drivers’ attention. It’s like saying, ‘We know we’re a hazard. We’re operating under DOT guidelines, and we are a hazard. Pay special attention.'”

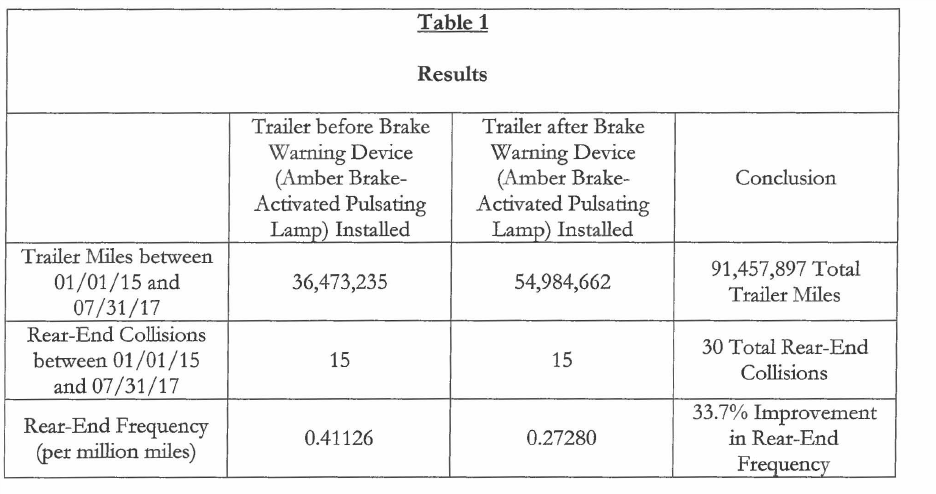

Groendyke had measured dispatch miles traveled by the trailers that had the lights, Gigoux said. The carrier measured 36.47 million miles without a strobe on some trailers, while trailers with strobes logged almost 55 million miles.

“We looked at accident frequency measured in miles of travel, and that’s where we saw the strobe versus the non-strobe trailers had 34% reduction in rear-end accidents,” Gigoux explained. “All accumulated, there’s roughly 80 to 90 million miles roughly involved of strobe and no strobes travel. We felt like that was a sizeable sample.”

Table: Groendyke’s Exemption Petition

Table: Groendyke’s Exemption Petition

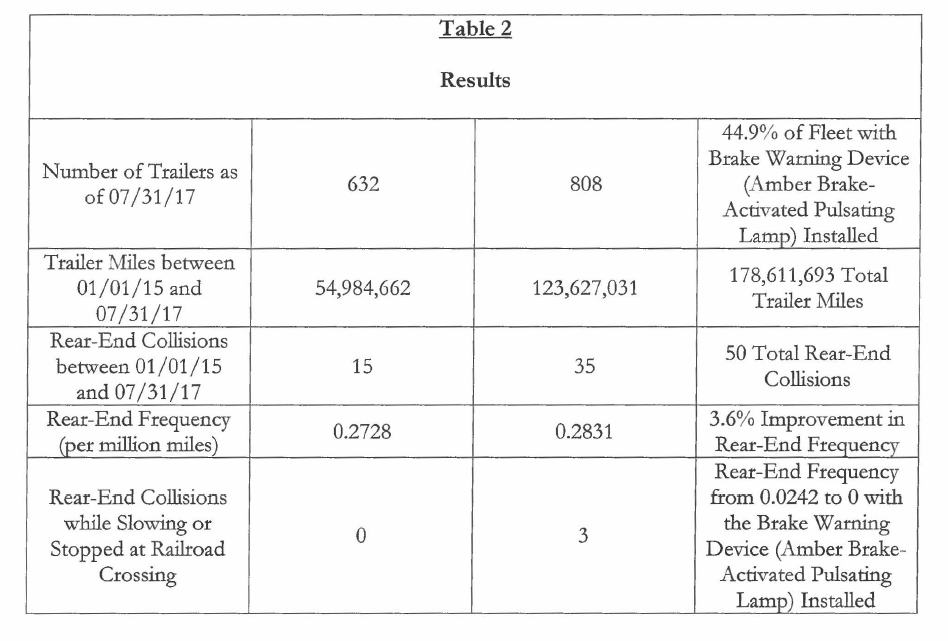

Rear-end collisions while stopped at railroad crossing dropped to zero, the company noted.

Table: Groendyke’s Exemption Petition

Table: Groendyke’s Exemption Petition

The cost of the strobe and installation is about $150, Gigoux said. After almost three years of testing, the fleet went full tilt on conversion and now has almost 900 trailers with the lights.

One of their hurdles was regulation. The fleet began testing the lights before receiving permission from the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA). Groendyke now has an exemption. (See petition here.)

“We were surprised at the number of violations we received during the test period. Once an inspector picks up on the fact that the light shouldn’t be blinking in the brake circuit, then it’s like they’re looking closely at every one of our trucks as they come through, and they’re going to write a ticket,” said Gigoux. “[Inspectors] flat out told our drivers, ‘every time you pull through here, we’re going to write you a violation.’ We would tell them that we’re testing this, and we think it’s going to bring a benefit. They would say: ‘I don’t care, it’s not in compliance.’ That’s what drove us to seek the exemption. We were successful in getting the exemption, and now [the idea of amber strobes] is really starting to grow.”

“We knew that we were a little bit rogue, but we were determined to improve safety,” he added. “We were determined to try to mitigate people from running into the back of us. Even if we didn’t eliminate people running into the back of us, we wanted to at least get them slowed down enough so there wouldn’t be serious personal injury. It’s two twofold. I think if there is one question out there for me it is how do we measure the near misses because you’ll never know about those since they are never reported.”

Groendyke’s experiment spurred interest from the rest of the tanker truck industry. The National Tank Truck Carriers (NTTC) last year petitioned FMCSA to allow pulsating, brake-activated lights. Current regulations prohibit blinking exterior lights except for turn indicators, oversized loads and a few other special situations.

This article was originally published by American Trucker.