As coronavirus worry spreads across the globe, the trucking industry and U.S. economy are facing uncertainty from several angles. There’s an oil war brewing. The stock market has seen its worst days since the 2008 financial crisis. Consumer spending is in jeopardy, which could affect freight rates. And there are growing concerns about how to limit human contact, which could hurt supply chains.

And while some companies are encouraging employees to work from home — that isn’t an option for truck drivers, technicians and others working in the industry. But for some, reduced imports from Asia this winter means less work in the U.S.

West Coast ports are the North American gateway for cargo from Asia. Over the past six weeks, operations at the ports have been increasingly impacted by the reduction of cargo flow from Asia as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak, according to the Pacific Maritime Association.

Cargo imports from Asia have fallen significantly over the past month, with work for longshoremen and drivers reduced up and down the coast, according to the Pacific Maritime Association. At the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, the two busiest in the U.S. and the main entry points for Chinese goods, work shifts have dropped 21% this year compared with the first quarter of 2019, according to the PMA.

Both facilities just released their February container volumes: Long Beach’s imports dropped 18% from a year earlier, L.A.’s fell 23%. That would be a drop of more than 500,000 container units, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Up to a million jobs in southern California could be affected by the coronavirus, according to the L.A. Times. Those jobs, tied into port activity, include those who work on the docks, drive trucks into and out of the ports, and those who move boxes in warehouses.

U.S. seaports could see slowdowns of as much as 20% continue into March and much of April, according to the American Association of Port Authorities. The same trend is seen in more distant places, with Rotterdam — Europe’s economic gateway to Asia and beyond — seeing a similar cut of about 20%.

“Once the virus is contained, we may see a surge of cargo, and our terminals, labor and supply chain will be ready to handle it,” says Mario Cordero, executive director at Long Beach.

But if that snapback doesn’t occur and the slump drags on for months, the economic and political importance of ports and their workers may rise to the forefront again in places that connect the U.S. to key markets overseas, such as Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia and Texas.

Up the West Coast in King County, Wash., where there have been 190 confirmed cases and 22 deaths as of March 10, the county fleet operations have Clorox wipes in each vehicle and are asking drivers to wipe down the inside at the start and end of each shift.

Trucking volumes up

Those Clorox wipes, bottles of Purell and other soaps and cleaners have been cleared off the shelves of stores across the U.S. by worried consumers, which has helped boost trucking volumes across the country, as freight rates rose the first full week of March, according to DAT Solutions, which operates the industry’s largest load board network.

At the start of the month, DAT reported no specific indications of supply chain disruptions due to the COVID-19 outbreak. But this may change in the coming weeks depending on import levels, how quickly Chinese ports can reduce their backlogs, and when those delayed sailings start to arrive at U.S. ports.

DAT Load Boards saw a 9.8% jump in loads posted during the week that ended March 8 — the largest was van loads, which were up 12.1% and the rates were up 2%. National spot rates had been falling since the year began — with each month since January posting a lower average national rate than the month before. March, which is only halfway over, could be the first month to see that average outpace the previous month.

Fuel prices down

Trucking is also benefiting from the brewing oil war, which has contributed to a steady decline in diesel prices across the country. At the start of the week, the average gallon of diesel in the U.S. cost $2.814 per gallon — 26.5 cents less than the first week of 2020, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. That’s the lowest national average since October 2017.

The U.S.’s position as the world’s top oil producer, a title held for more than two years, is now at risk. Saudi Arabia had orchestrated output curbs with Russia that helped prop up prices. But the Saudis are now threatening to flood the world with oil after its production pact fell apart, putting prices are in free-fall, which cut prices in half in two months to around $30 a barrel.

Most shale wells are now unprofitable and drillers are scrambling to scale back operations. At $35 a barrel, U.S. output — now about 13 million barrels a day — could fall by 1 million barrels this year, according to BloombergNEF, and by 2.5 million in 2021, said Scott Sheffield, who heads one of the biggest independent shale producers. Meanwhile, the Saudis have vowed to supply 12.3 million barrels daily.

“It’s all about getting by,” Sheffield, the chief executive officer at Pioneer Natural Resources Co., said in an interview Tuesday on Bloomberg TV. He sees most companies “going into maintenance mode” until prices rise, adding, “nobody wants to increase the balance sheet in this environment.”

Are your employees at risk?

The new coronavirus causes little more than a cough if it stays in the nose and throat, which it does for the majority of people unlucky enough to be infected. Danger starts when it reaches the lungs.

One in seven patients develops difficulty breathing and other severe complications, while 6% become critical. These patients typically suffer failure of the respiratory and other vital systems and sometimes develop septic shock, according to a report by last month’s joint World Health Organization-China mission.

About 10-15% of mild-to-moderate patients progress to severe and of those, 15-20% progress to critical. Patients at the highest risk include people 60 and older and those with pre-existing conditions such as hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

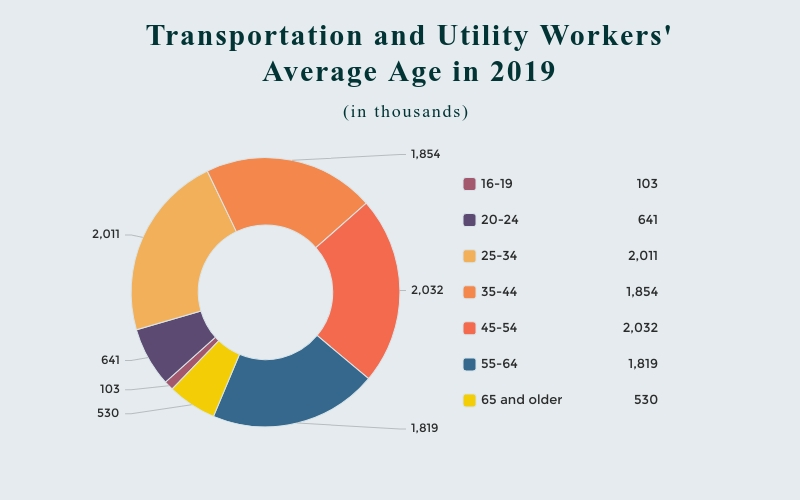

Most truck drivers and utility workers are between 25 and 64 years old, according to labor statistics. But nearly 6% are 65 and older, which makes them more susceptible to the virus. Adding to that risk is that a higher percentage of drivers suffer from diabetes or a considered pre-diabetic. Nearly one in three drivers examined for CDLs between 2014 and 2017 were found to be pre-diabetic or pre-hypertensive (high blood pressure).

Data taken from The Bureau of Labor Statistics: 2019 household data annual averages of employed persons by detailed industry and age.Chart: Catharine Conway/Fleet Owner

Data taken from The Bureau of Labor Statistics: 2019 household data annual averages of employed persons by detailed industry and age.Chart: Catharine Conway/Fleet Owner

As of today, more than 121,000 cases have been confirmed worldwide, taking the lives of more than 4,300 people — according to the real-time tracker of the coronavirus created by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University – making the overall death rate 3.55%.

COVID-19 most likely spreads via contact with virus-laden droplets expelled from an infected person’s cough, sneeze or breath. Infection generally starts in the nose. Once inside the body, the coronavirus invades the epithelial cells that line and protect the respiratory tract. If it’s contained in the upper airway, it usually results in a less severe disease.

But if the virus treks down the windpipe to the peripheral branches of the respiratory tree and lung tissue, it can trigger a more severe phase of the disease. That’s due to the pneumonia-causing damage inflicted directly by the virus plus secondary damage caused by the body’s immune response to the infection.

“When you get a bad, overwhelming infection, everything starts to fall apart in a cascade,” said David Morens, senior scientific adviser to the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “You pass the tipping point where everything is going downhill and, at some point, you can’t get it back.”

That tipping point probably also occurs earlier in older people, as it does in experiments with older mice, said Stanley Perlman, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, who has studied coronaviruses for 38 years.

COVID-19 fatality rate

According to COVID-19 fatality rate, the average age of those who succumb to the virus is 77 years old — but it’s 68 years old for the men who have died and 82 years old for women.

Currently, a vaccine or drug is not available for COVID-19, according to the CDC. Community-based interventions such as school dismissals, event cancellations, social distancing, and creating employee plans to work remotely can help slow the spread of COVID-19. Individuals can practice everyday prevention measures like frequent hand washing, staying home when sick, and covering coughs and sneezes.

In accordance with these instructions, Amazon has taken measures to inform and protect its drivers and the community. Amazon sent an email to its trucking network on March 3 with advice on how to conduct business amid coronavirus concerns. The email advised truckers to stay home for at least 24 hours if feeling feverish, to frequently wash one’s hands, and to regularly disinfect steering wheels and other often-touched parts of the truck.

However, the increased panic in the U.S. has led to high demand for disinfecting products from retail shelves in an almost record speed. From Clorox wipes and disinfecting alcohol to toilet paper, Americans are stocking up on supplies in the event they are forced to self-quarantine for the aforementioned 14-day time frame.

Empty Stop and Shop shelves in Tarrytown, NYPhoto: Teresa Sopot

Empty Stop and Shop shelves in Tarrytown, NYPhoto: Teresa Sopot

No matter what reaction the public takes on the now-coveted household supplies, the CDC urges that the best action to take against coronavirus is thoroughly washing your hands. “Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds especially after you have been in a public place, or after blowing your nose, coughing, or sneezing.”

Reporting from Bloomberg News services contributed to this article.

This article was originally published by American Trucker.